Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

On May 24th, 2001, around 700 guests gathered in the Versailles Wedding Hall in the Talpiot neighborhood of Jerusalem to celebrate the wedding of Keren and Asaf Dror.

Hundreds filled the dance floor, moving joyfully to “Lev Zahav” by Sarit Hadad.

The Collapse

At exactly 10:43 PM, disaster struck.

Without warning, the dance floor on the third story collapsed, sending dozens of people plummeting through two stories below.

There was a deafening crash. The room filled with screams, dust, and shattered concrete.

Within seconds, joy had turned to horror.

The tragedy left 23 people dead—including the groom’s grandfather and a three-year-old cousin. Around 350 to 380 people were injured, making it the third deadliest civil disaster in Israeli history.

Immediate Aftermath

The bride sustained severe pelvic injuries requiring multiple surgeries.

The entire collapse was caught on video by cameraman David Amromin. The footage, showing a joyous dance followed by sudden catastrophe, would later spread worldwide.

Rescue efforts were carried out by Home Front Command with their Search and Rescue Unit, who dug through rubble with their bare hands in fear that the rest of the building would collapse.

Operations continued until 4 PM on May 26th. Miraculously, three people were pulled alive from the rubble.

Searching for Answers

In the chaos that followed, many initially suspected terrorism—the disaster occurred during the Second Intifada.

But engineers quickly uncovered the true cause: a faulty construction method called Pal-Kal.

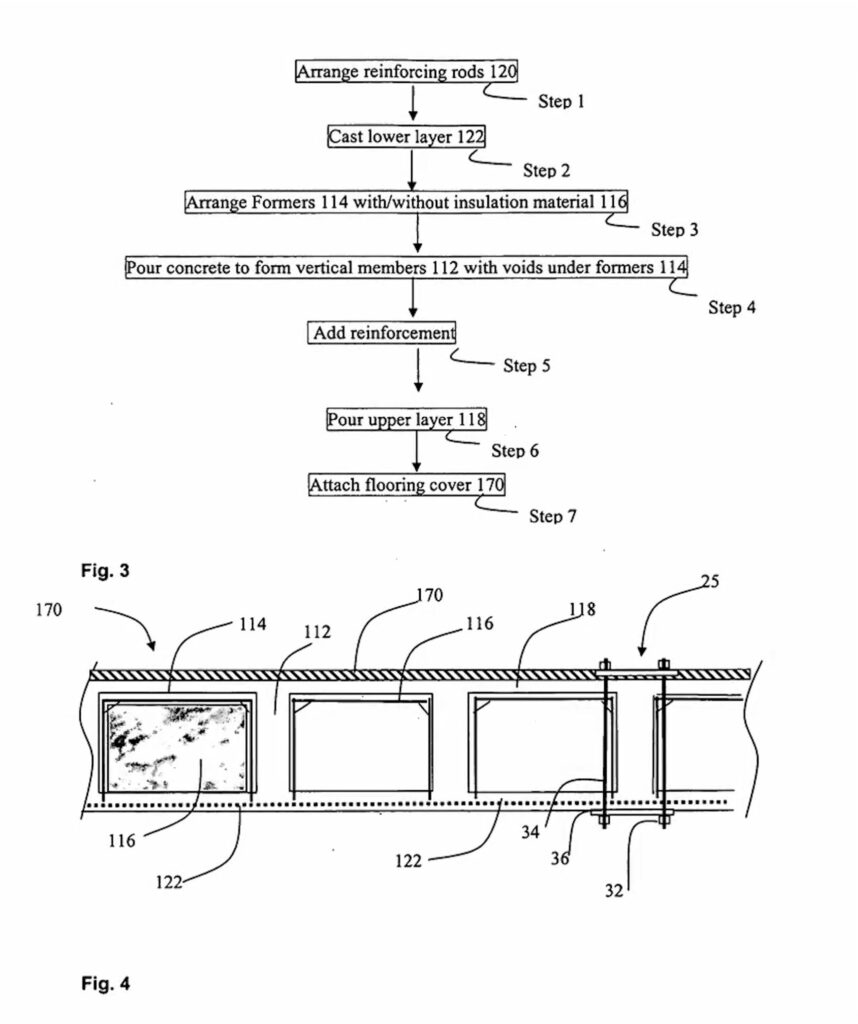

Developed in the 1980s by engineer Eli Ron, Pal-Kal used thin concrete slabs supported by metal panels, with minimal reinforcement. It was cheap and fast—but dangerously unstable under heavy loads.

By 1996, mounting safety concerns led the Israel Standards Institute to ban Pal-Kal in new construction. Still, thousands of existing structures—including the Versailles Hall—remained in use.

Fatal Design Flaws

Originally, the building was designed with one side two stories tall and the other side three. Midway through construction, the owners decided to even it out by adding a third story to the shorter side.

But the supporting structures were never fully reinforced, causing the floor to sag. Temporary stability came from internal partitions on the floor below, which redistributed the weight.

A few weeks before the wedding, the owners removed those partitions.

They saw the sagging floor as a cosmetic issue and attempted to fix it with grout and fill. Instead of strengthening the structure, this added more dead weight to an already compromised floor.

It was a ticking time bomb.

Legal Consequences

In 2002, the three co-owners of the hall—Avraham Adi, Effraim Adiv, and Uri Nissim—were indicted.

Two years later, they were convicted of causing death by negligence. Adi and Adiv received 30 months in prison, while Nissim served four months of community service.

Eli Ron, the inventor of Pal-Kal, was also convicted. In 2007, he was sentenced to four years in prison. Several engineers involved in the hall’s construction received jail terms ranging from six to 22 months.

The court concluded that greed, corner-cutting, and neglect were at the root of the collapse.

The Versailles Law

In the wake of the disaster, Israel’s Parliament passed the Versailles Law, creating a special compensation fund for victims and enforcing stricter construction oversight.

In 2016, the state reached a settlement with 428 victims and families, paying out a total of 120 million shekels (about $32 million USD).

Compensation was determined by injury severity, hospitalization costs, and funeral expenses.

Lasting Impact

The Versailles Wedding Hall disaster exposed deep flaws in Israel’s construction oversight and highlighted the dangers of prioritizing profit over safety.

The site was eventually demolished, but across the street, a small memorial now bears the names of the 23 victims.

Hundreds of other Pal-Kal buildings across Israel were re-inspected—some reinforced, others condemned. Building codes were revised, inspectors gained more authority, and architects and engineers were reminded of a painful truth: shortcuts in construction can cost lives.