Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

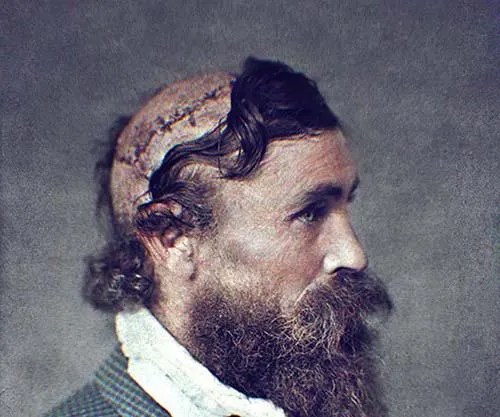

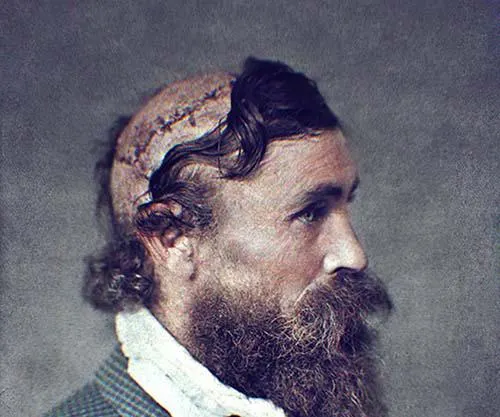

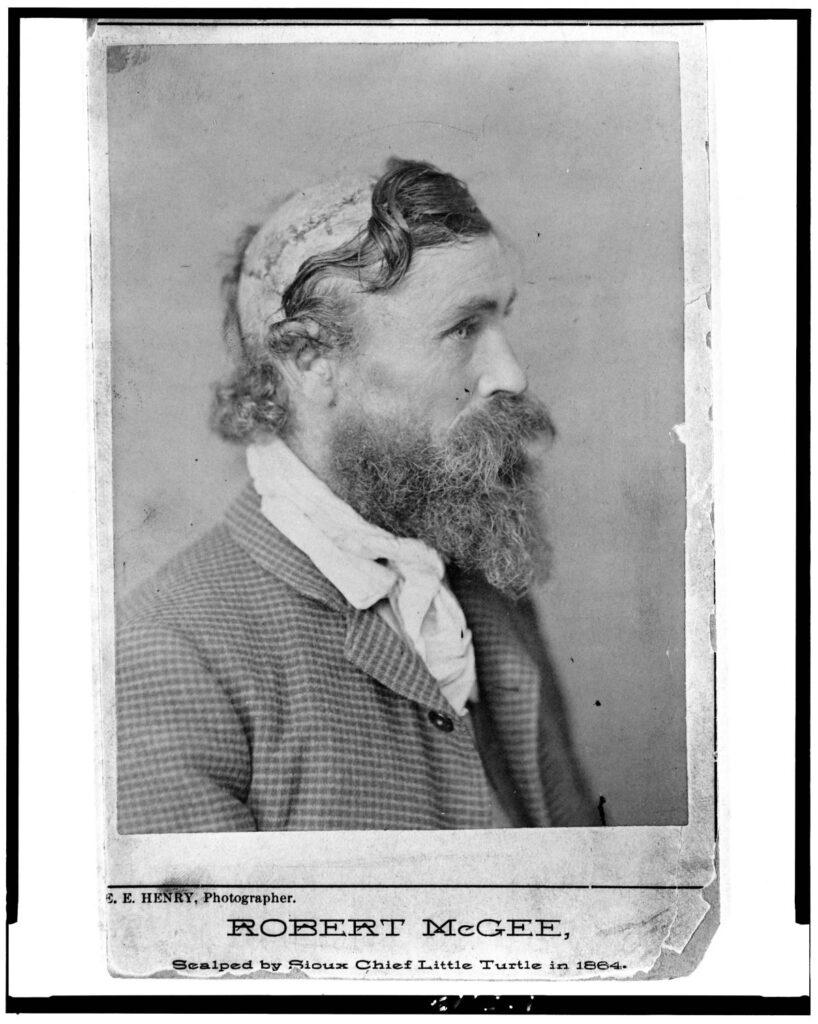

In 1864, 14-year-old Robert McGee was scalped on the Santa Fe Trail—and survived. His shocking 1890 portrait tells the chilling true story.

In the summer of 1864, on the perilous expanse of the Santa Fe Trail, a teenage boy named Robert McGee endured one of the most horrifying fates imaginable—and survived to tell the tale. Scalped alive during a brutal attack, McGee’s story has haunted historians and readers for over 150 years. Decades later, his portrait would shock the world, immortalizing his suffering and resilience as one of the most chilling images of the American frontier.

The mid-19th century was a volatile time in the American West. The Santa Fe Trail, stretching from Missouri to New Mexico, served as a critical artery for trade, migration, and military supply. But it was also fraught with danger. By 1864, tensions between Native tribes, settlers, and the U.S. military had escalated into open conflict. Wagon trains moved cautiously, often under the protection of soldiers.

Among those journeying westward was Robert McGee, a boy of just 13 or 14 years old. He and his family joined a wagon train headed toward Leavenworth, Kansas, seeking opportunity on the expanding frontier. The journey, however, proved deadly—McGee’s parents died along the way, leaving him orphaned.

When he arrived at Fort Leavenworth, the boy attempted to enlist in the U.S. Army but was turned away for being underage. Instead, he was hired as a teamster by the H.C. Barret Company to help transport flour to Fort Union in New Mexico Territory. It was a decision that would lead him directly into one of the most infamous attacks in frontier history.

By midsummer, the caravan had settled into a grueling rhythm, covering roughly 16 miles a day under the blazing Kansas sun. On one particularly hot day in July 1864, the teamsters made camp near Walnut Creek, close to present-day Great Bend, Kansas. Believing they were safe—only a mile or so from a nearby military presence—they began to relax.

But their sense of safety was an illusion.

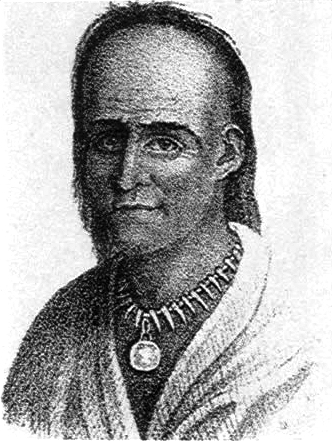

Around 5 o’clock in the evening, roughly 150 Sioux warriors, reportedly under the leadership of Chief Little Turtle, descended upon the camp. The assault was sudden and devastating. The warriors slaughtered the teamsters and destroyed everything in sight—tearing wagon covers to shreds, scattering flour along the trail, and setting fire to anything that would burn.

In the chaos, Robert McGee was struck by multiple arrows, shot in the back, and hit with a tomahawk. Gravely wounded, he collapsed face-first into the dirt but remained conscious.

Chief Little Turtle, according to later accounts, approached the wounded boy and—with a single deliberate stroke—cut a massive portion of scalp from McGee’s head, reportedly sixty-four square inches, beginning just behind his ears. Unlike the smaller scalp patches sometimes taken by other tribes, this was an unusually large section, leaving his skull completely exposed.

McGee’s body was left among the dead, assumed to be lifeless. But fate had other plans.

Just two hours after the massacre, scouts from Fort Larned—having been warned that Sioux warriors were on the warpath—arrived at the scene. They discovered a grisly sight: the grass soaked in blood, bodies scattered and mutilated. Every victim had been scalped.

Amid the carnage, the scouts found two boys still breathing. Both had been scalped and suffered multiple wounds. They were rushed back to Fort Larned, where one soon died. The other—Robert McGee—miraculously survived.

Frontier doctors treated his wounds as best they could, keeping infection at bay and allowing the raw scalp tissue to heal. Though he would forever bear the physical reminder of his ordeal, McGee defied the odds and made a full recovery.

While the act of scalping sounds instantly fatal, survival was possible if the skull remained intact and bleeding could be controlled. In McGee’s case, his youth, the quick intervention of rescuers, and sheer resilience likely saved him. The wound left him permanently bald on top of his head, with only a thin ring of hair remaining—a living testament to his ordeal.

Roughly 25 years later, around 1890, Robert McGee sat for a studio portrait. The photographer, believed to be E.E. Henry, captured McGee in a stark profile view that revealed the full extent of his injury—a smooth, healed scalp where hair could never grow again.

The image is among the most haunting ever taken of a human survivor. Newspapers and magazines of the late 19th century widely circulated it, turning McGee into both a curiosity and a symbol of the brutality that defined the American frontier. Today, the photograph resides in the Library of Congress and Wikimedia Commons, serving as a sobering piece of visual history.

After recovering, Robert McGee lived quietly for decades. Records suggest he eventually settled in Excelsior Springs, Missouri, where he lived out his life away from the public eye. Though his personal details remain sparse, his image and story endured long after his death, appearing in history books, magazines, and later—across the internet.

Historians warn that many retellings of McGee’s ordeal contain exaggerations. Some accounts inflate the number of attackers or dramatize the role of specific chiefs. Others weaponize the story to portray Native Americans as purely savage, ignoring the broader reality of U.S. expansion, broken treaties, and retaliatory violence that defined the era.

Despite these embellishments, the core facts are undeniable:

Robert McGee was scalped as a teenager on the Santa Fe Trail in 1864.

He survived.

And his photograph remains one of the most powerful testaments to both human cruelty and endurance ever captured.