Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

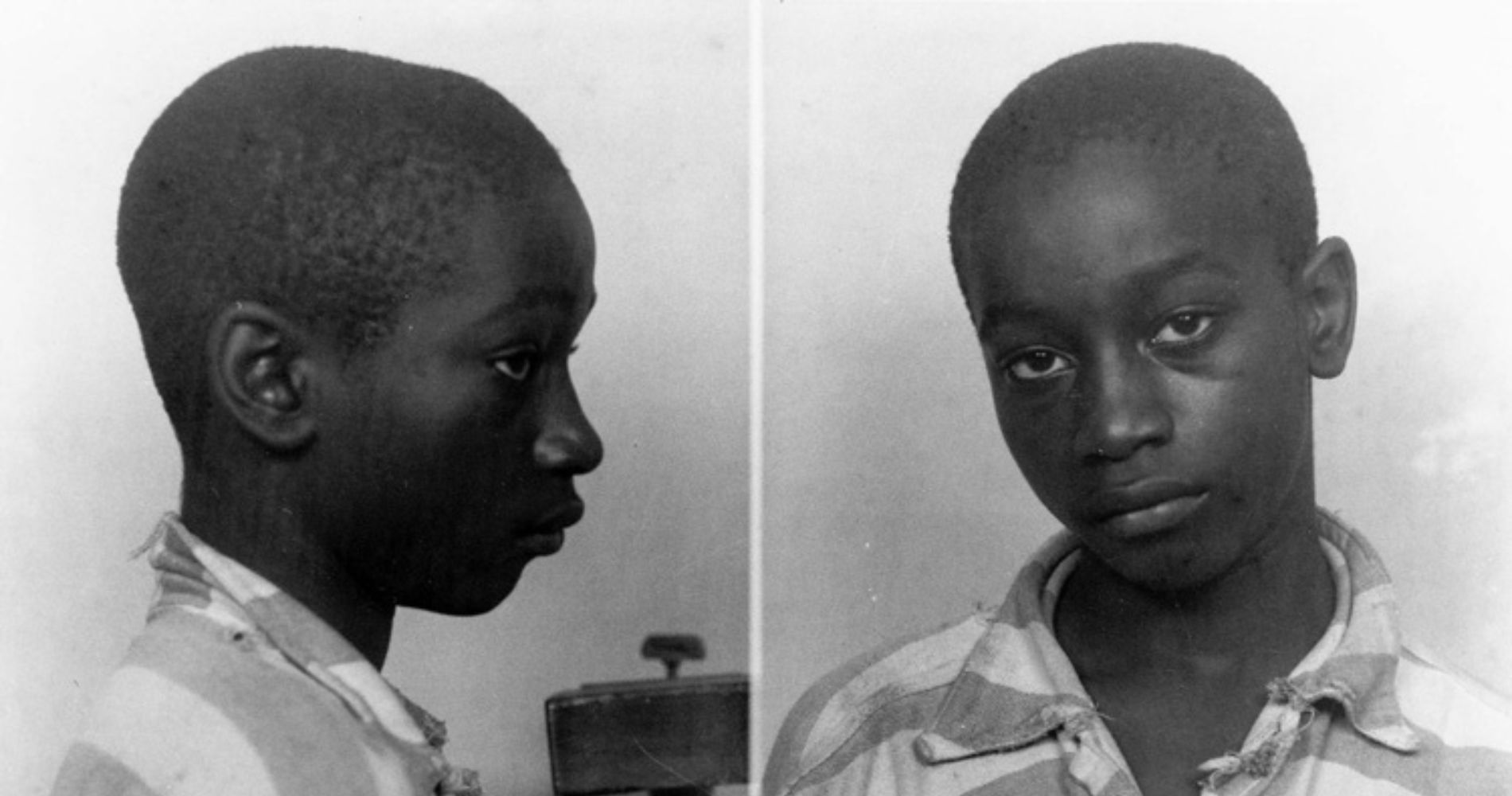

At just 14 years old, George Stinney Jr became the youngest person executed in U.S. history. His case — a story of racial injustice, wrongful conviction, and eventual exoneration — remains one of the darkest examples of Jim Crow–era America.

It took only 10 minutes to convict him. It took 70 years for the truth to come out.

George Stinney Jr. was only 14 years old when he was executed in 1944 — becoming the youngest person executed in the United States during the 20th century. His story embodies the cruelty and racial injustice of the Jim Crow South, and his wrongful execution remains a haunting symbol of America’s failed justice system.

In 1944, the small mill town of Alcolu, South Carolina, was literally divided by railroad tracks — white families on one side, Black families on the other. Segregation ruled every part of life.

On the Black side lived George Junius Stinney Jr., a quiet and intelligent boy who enjoyed drawing and riding his bicycle. Born on October 21, 1929, George was the son of a sawmill worker and stood only five feet tall, weighing 90 pounds.

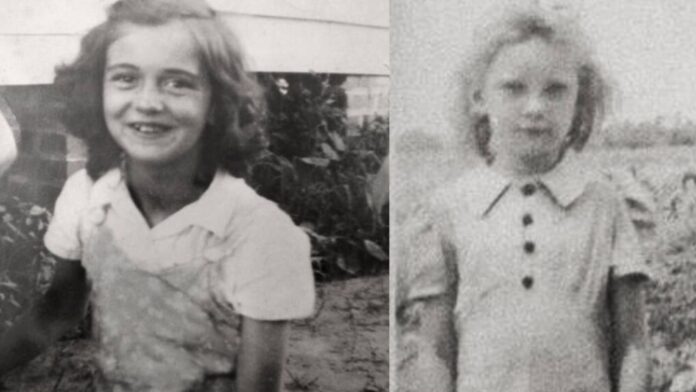

That spring, two white girls — Betty June Binnicker (11) and Mary Emma Thames (7) — went missing while riding their bicycles near the Black neighborhood. Their disappearance would trigger one of the most infamous wrongful convictions in American history.

On March 23, 1944, Betty and Mary Emma rode into the Black section of town, asking if anyone knew where to find “maypop” flowers — passionflowers that grew nearby. They spoke briefly with George and his sister Amie outside their home before riding off.

By nightfall, the girls had not returned. A search party was formed, and George Stinney and his father joined the effort. George even mentioned that he had seen the girls earlier that day.

The following morning, the girls’ bodies were found in a muddy ditch beside a railroad embankment. Both had been beaten to death with a blunt object, their skulls crushed. Investigators suspected a piece of iron, possibly a railroad spike, had been used as the weapon.

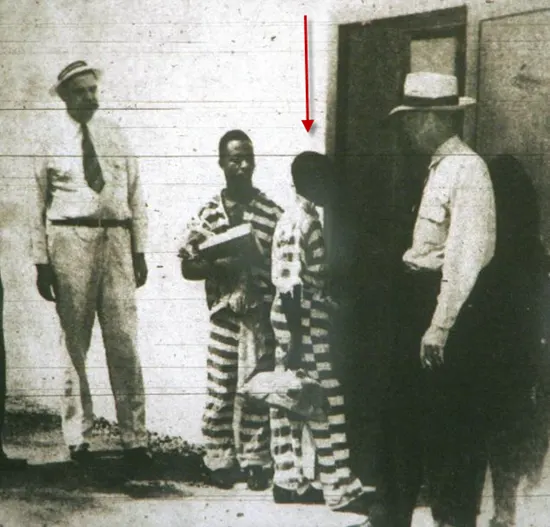

Later that day, without evidence or a warrant, police arrived at the Stinney family home and took George into custody. He was just 14 years old.

After his arrest, his father was fired from his job at the sawmill, and the family was evicted from their company-owned home. Fearing mob violence, they fled Alcolu and never saw George again before his trial.

George was held in isolation at a jail in Columbia, 50 miles away. Police interrogated him without a lawyer, parent, or transcript. Officers later claimed he confessed to killing the girls — but no written confession, no signed statement, and no physical evidence ever existed. The alleged confession came only from the white officers’ testimony.

This so-called “confession” became the foundation of a wrongful conviction that would end in the execution of a child.

George’s trial began on April 24, 1944 — less than a month after his arrest.

His court-appointed defense attorney, Charles Plowden, was a tax commissioner campaigning for local office, not a criminal defense lawyer. He called no witnesses, cross-examined no one, and failed to challenge inconsistencies in the prosecution’s story.

The prosecution relied solely on the officers’ testimony of George’s “verbal confession.” No murder weapon was found. No physical evidence linked George to the crime scene.

Over 1,000 white spectators packed the courtroom, while Black residents were barred from entering. The all-white, all-male jury deliberated for less than 10 minutes before declaring George Stinney Jr. guilty of murder.

Judge P.H. Stoll sentenced him to death by electric chair.

He was only 14 years old.

On the morning of June 16, 1944, George Stinney Jr. was escorted into the execution chamber at the South Carolina State Penitentiary.

Because he was so small, guards placed a Bible on the seat to raise his height. He was strapped down tightly — arms, legs, and torso. When asked for final words, George softly replied, “No, sir.”

As the executioner placed the oversized leather mask over his face, tears streamed down George’s cheeks.

At 7:30 a.m., 2,400 volts of electricity were sent through him in three bursts. Witnesses said his small frame shook violently before he went still.

He was pronounced dead minutes later.

George Stinney Jr., the youngest person executed in the United States, was gone.

For decades, the case was buried. Then, in the early 2000s, civil rights advocates and organizations like the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) began investigating.

In 2013, George’s siblings filed a motion to reopen the case, presenting alibi testimony that George had been with his sister Amie when the girls were killed.

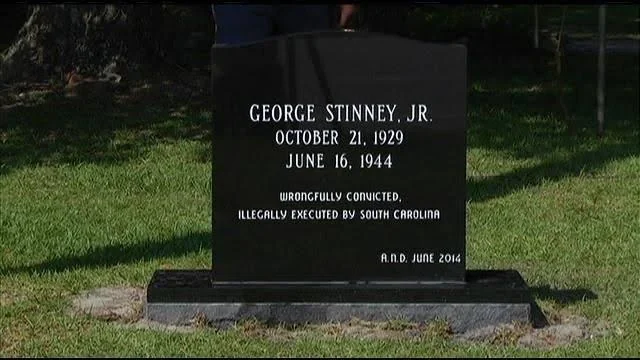

On December 17, 2014, Circuit Judge Carmen T. Mullen overturned the conviction, ruling that Stinney’s trial was fundamentally unfair.

“The confession cannot be said to be known and voluntary,” Mullen wrote. “The defendant was without effective assistance of counsel. His conviction was fundamentally flawed.”

After 70 years, George Stinney Jr. was officially exonerated.

After the exoneration, speculation grew that George Burke Jr., the son of a wealthy white businessman, might have been involved in the murders.

Burke Jr. died in 1947, only three years later. Stinney’s mother had worked briefly for the Burke family and reportedly told her children that Burke Sr. had made inappropriate advances toward her.

Burke Sr. also owned the land where the girls’ bodies were discovered and served as foreman of the grand jury that indicted George — a serious conflict of interest.

Local residents described Burke Jr. as a known womanizer and troublemaker who was rarely held accountable for his actions.

In later years, Sonya Eaddy-Williamson, an Alcolu resident close to Stinney’s family, claimed that Burke Jr.’s son, Wayne Burke, told her that his grandmother had once admitted that Burke Jr. picked up the girls in his lumber truck that day. Wayne has since denied the claim, insisting Stinney was guilty.

Rumors of a deathbed confession by a prominent white local have circulated for decades, though no evidence has ever confirmed it.

The George Stinney Jr. case remains one of the most disturbing examples of racial injustice in American history. His execution exposed how deeply racism and fear corrupted the legal system under Jim Crow laws.

In 2005, the U.S. Supreme Court ruling Roper v. Simmons made it unconstitutional to execute anyone under 18 — a safeguard George never had.

Today, a memorial headstone in Alcolu honors his name and reads:

“Wrongfully convicted. Exonerated.”

The story of George Stinney Jr. is not just about a boy — it’s about a system that failed him. It’s a reflection of how prejudice can distort truth and how justice can be denied to those without power or protection.

In the ongoing struggle for racial equality and criminal justice reform, George’s name remains a reminder of why truth and fairness must prevail.

He was only 14 years old.